Legal Precedents

Numerous lawsuits regarding artistic copyright and fair use have occurred in the US, setting some legal precedents for the creation and ownership of AI-generated art. Yet such cases, including the two described below, illustrate the gray area of the law in which the processes of artmaking and inspiration-seeking often find themselves.

Rogers v Koons

In 1988, pop artist Jeff Koons created and sold a series of sculptures titled “String of Puppies,” which were based on a photograph by Art Rogers. Koons sold the works for $375,000, and Rogers sued with the claim that his copyrighted photo was reproduced without permission. Supporting evidence included messages sent by Koons telling his workers that the “String of Puppies” sculptures should be just like Rogers's image. Despite the suggestion that the photo would be directly copied, Koons's notes also included details about how to alter the subject in cartoonish ways that would make his work distinct from the photo.

"Puppies" by Art Rogers, 1985

Koons's defense argued that a sculpture was transformative enough in nature from a photograph to be considered fair use, and that the image was simply treated as a fragment of information in a broader landscape of popular culture, so the expressiveness—and therefore the artistic nature of Rogers's work—was not infringed upon. The sculpture not only depicted the same subject in an entirely different medium, but also injected an unnerving quality that distinguished its artistic expression from that of the photograph.

"String of Puppies" by Jeff Koons, 1988

At the time, the appropriation of images had been on the rise for decades in the art world, as artists looked for subjects in popular culture and often created parodies or social commentaries with the use of trademarked work. The tension between artistic freedom and copyright was not new, but the question of which side would prevail legally remained unanswered. Harvard Law professor Kathleen Sullivan asked: “Will the Rogerses of the world be intimidated if they're not protected from theft, or will the Koonses of the world be stymied because their sources are cut off? It's a tossup.”

In 1990, a judge ruled that Koons's sculpture was similar enough to Rogers's photo to be considered a copy. Koons appealed the court the next year, and his defense made critical arguments for contemporary art: “This Court must attempt to reconcile the fair use doctrine with various widely recognized elements of what is called the post-modern art movement. More so than their traditional forebears, post-modern artists incorporate in their works existing art and commercial images, thereby putting these artists on an apparent collision course with the Copyright statute…the fair use doctrine must be flexible enough to encompass and thereby not discourage these new and legitimate art forms.” Rogers's side argued that such a flexible definition of fair use would encourage appropriation because artists would no longer need to prove that the purpose of their works necessarily requires the copying of trademarked works. Koons's lawyers asserted that Rogers's photo was necessary to the work which aimed to draw out the flavors of mass production embedded in it. The court again ruled in Rogers's favor, citing the similar characteristics between the works' subjects.

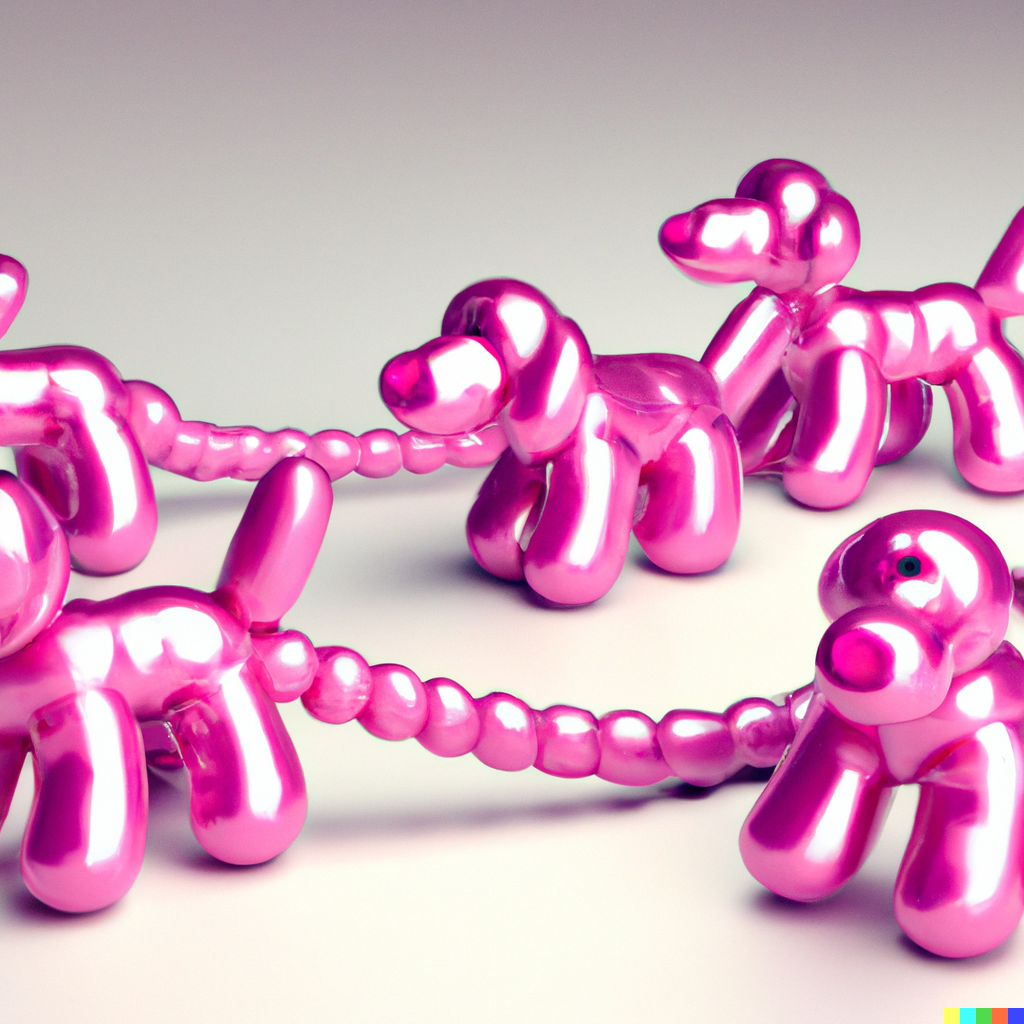

"String of pink puppies in the style of Jeff Koons," DALL-E 2, 2022

Warhol v Goldsmith

In 1981, photographer Lynn Goldsmith took studio and concert photos of Prince for Newsweek. A concert photograph was used for the publication, so Goldsmith kept the studio photos for later use. Three years later, Vanity Fair commissioned Andy Warhol to create a piece for an article about Prince, using one of Goldsmith's photos as a reference. Goldsmith was paid $400 in licensing fees with the promise of using the image only in the article.

Despite the agreement, Warhol created 16 silkscreens using Goldsmith's photo, one of which was used for the Vanity Fair article. Since then, the 16 images have been continuously reproduced by the Andy Warhol Foundation for hundreds of millions of dollars in profit. One of the images was again used in an issue of Vanity Fair after Prince died in 2016, with the magazine paying over $10,000 to print the work. Goldsmith received neither fee nor credit, and eventually sued the Andy Warhol Foundation, claiming that Warhol infringed upon her copyright.

Portrait of Prince by Lynn Goldsmith, 1981 (left). 16 silkscreens of Prince by Andy Warhol, 1984 (right).

The case is pending in the Supreme Court in 2022. The Warhol side argues that, in addition to Warhol having copyrighted the Prince series, his work falls under transformative use because it is different in media and artistic expression. Warhol not only cropped, resized, and rotated the image, he also altered the shading and used bright colors in his pieces. The Foundation argues that the result is “flat, impersonal, disembodied, [and] masklike;” in other words, its expressive goals and qualities are fundamentally different from Goldsmith's photo.

So far, judges have ruled for both sides, which has led the case to the Supreme Court. The decision could shift copyright law and fair use to the benefit of either side, with significant consequences for artists and other creators either way.

"Purple rain in the style of Andy Warhol," DALL-E 2, 2022

The reuse of images has only expanded since the Rogers v Koons decision, and disagreement among lower courts has led Warhol v Goldsmith to the Supreme Court, where a decision is still awaited. These famous cases resemble each other as they question the extent of fair and transformative use in the art world, with compelling arguments and serious concerns on both sides. Evidently, the tension between artistic freedom and copyright law remains unresolved as the Internet and AI-generated art perpetuate the conflict.